What languages are spoken in Belgium? Actually, Belgium has three official languages: French, Dutch and German.

Dutch is almost identical to Dutch, except for some local terms and expressions, but some Dutch areas of Belgium have local dialects that may not be understood by Dutch-speakers at times.

Table of Contents

Official languages

The French spoken in Belgium is fluent French, but it is distinguished by its accent (at least the opinion of the French!) And a few specific words, including the use of septante and nonante for 70 and 90 instead of soixante-dix and quatre-vingt dix . (Curiously, the Belgians employ quatre-vingt for the number 80 and not huitante , which is used in Switzerland and other French-speaking regions of the world).

Almost 60 per cent of the Belgian population speaks Dutch as their first language, 40 per cent is French-speaking, and there is a small area in the east (which accounts for less than 2 per cent of the population) along the German border where we speak German.

The division of Belgium

Explaining the linguistic map of Belgium without first explaining to you how the country is structurally organized is impossible. You may have already heard about our federal, federal, community or linguistic (or all) political woes (yes, it’s possible: it’s called the “municipalities with facilities”) and I’ll come back to that. ) and if so, you probably already hate me.

The Kingdom of Belgium therefore has three groups of speakers who speak these three different languages and have been given a constitutional, political and legal existence. We therefore speak of the Flemish Community(which speaks Dutch), the French Community and the German-speaking Community .

Photo credits (creative commons): Vascer

Photo credits (creative commons): Vascer

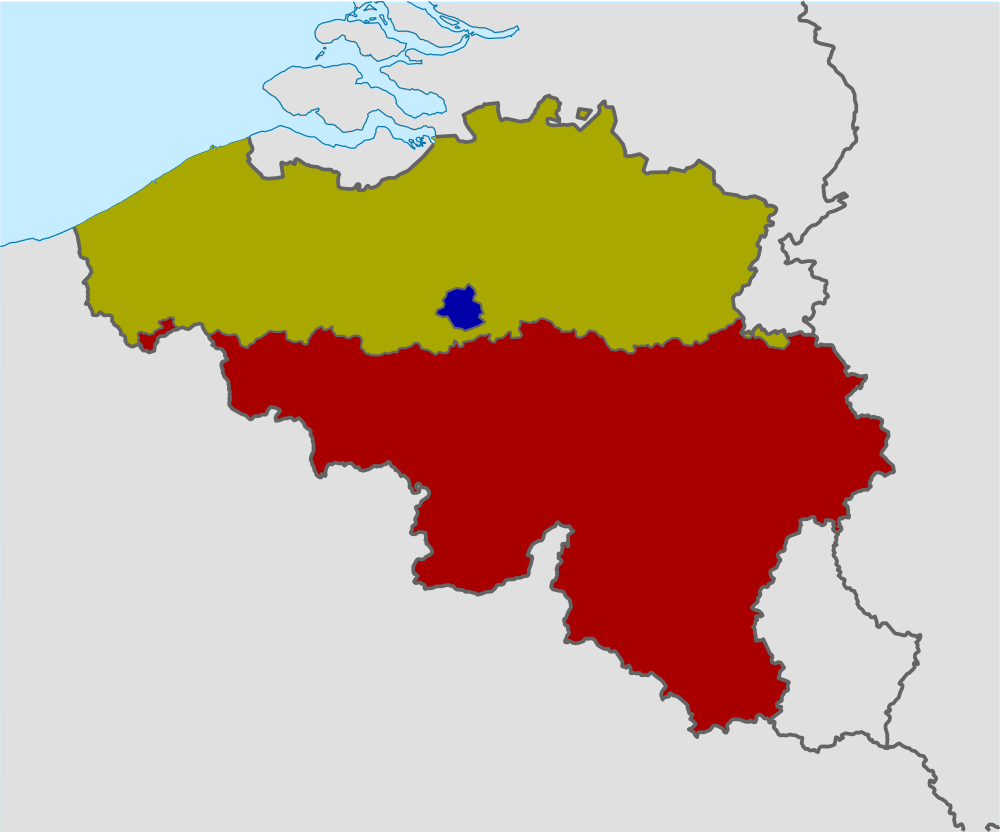

In green: the Flemish Community – In red: the French Community

In blue: the German-speaking Community

Since it was too easy for us, we have another level of division: the regions. We have three, the Walloon Region(Wallonia), the Flemish Region (Flanders) and the Brussels-Capital Region . It is exclusively a geographical division.

Photo credits (creative commons): Vascer

Photo credits (creative commons): Vascer

In green: the Flemish Region – In blue: the Brussels-Capital Region – In red: the Walloon Region

Communities, although linguistic, have been “assigned” to geographical areas. This means that the Flemish Community covers the Flemish Region, of course, but also the Brussels-Capital Region, which is bilingual since it is the capital of the country. The Walloon Region contains both the German-speaking Community and the French Community. The latter also has the “other half” of the Brussels-Capital Region.

Languages, sources of conflict?

It is often said that there are 60% Flemish, 40% French and less than 1% German speakers in Belgium. The Constitution does not allow linguistic censuses (the bad languages claim that it is to avoid a disappointment in Flanders!), But it is common to say that the Francophones are actually more numerous.

Brussels crystallizes tensions at this level because, although bilingual on paper, nearly 90% of the population is French speaking or uses French as a lingua franca.

The growing population of the capital eventually “colonize” the periphery: Brussels being landlocked in the Flemish Region, it caused the creation of “communes with facilities”. These are Flemish municipalities along Brussels, in which each inhabitant can choose his “language regime”, that is to say in what language he will receive and carry out the administrative procedures, if he can vote for the French-speaking parties or Flemish, etc.

There are many community conflicts in Belgium, based on linguistic quarrels, political disagreements and cultural differences. Who from the egg or the hen has provoked them, it is difficult to determine. One thing is certain: living in a multilingual country means first and foremost experiencing “different cultures” (in my opinion, it is the source of many problems).

A Flemish has a different culture than a francophone, and vice versa. We can identify personalities and affinities specific to each community:

- The Flemish are known to be colder and more serious, and the French are supposedly more open and less “headache”.

- The Flemings have a true culture of celebrity (reality TV and magazines galore), where Francophones are much less sensitive to the star system.

- The French-speaker is known to make little effort in foreign languages, when the Flemish easily master two or three.

- Finally, the Flemings have a decidedly Germanic culture, while Francophones are much more influenced by the Latin side.

The languages of Belgium

Belgians say that they speak “Dutch”, “French” or “German”, but in reality, our speech is different from that of the country of origin of each of these languages. The main reasons are obviously the contact with the other languages, but also the fact that, thus cut off from the mother-tongue by borders, each language has evolved differently.

You probably know some examples of francophone belgicisms. The best known are often “septante” and “nonante” (70 and 90), or our “déjeuner, dîner, souperr” (morning, midday and evening meals). But we also use the revered ” filet américain” (steak tartare, very appreciated here), the “drache” (a big rain, which is also declined in: “Tiens, il drache !” To say that it rains) or the “Kots” (dwellings inhabited by students).

Attention, the expression “une fois” is practically not used in French in Belgium: it is actually a translation made by the Flemings of one of their expressions. Say “une fois!” To laugh at a French speaker in Belgium does not make much sense: it speaks to him about as much as to a Marseillais. Here you are!

Finally, just as there is not only one French accent in France, there is not only one Belgian accent in Belgium, and it is all the more true that there are three spoken languages. The “Belgian” accent to which you think certainly imitates a Flemish trying to speak French, or a (very) old Brussels native!

In the French Community, for example, one easily identifies the Liege accent, which is very pronounced ( you can listen to it here ), or that of the province of Hainaut, which resembles the Picard of northern France. The inhabitants of Brussels have a sort of “neutral” accent in the ears of other regions, which is actually closer to French in France. It is not uncommon for a Brussels resident to be asked by a Liegeois: “Are you French, in fact? (It’s real life.)

Living in a multilingual country means …

Living in a multilingual country like Belgium means living in a “world” separate from that of your neighbor. Inter-community exchanges are infrequent because of the language barrier. Brussels residents and those working in Brussels are easily in contact with the other community, but we do not really mix.

The teaching of French is for example compulsory in the Flemish Community, but that of Dutch is not compulsory in Wallonia (but it is in Brussels!). We find ourselves de facto in a situation where many Flemings manage to hold at least a small conversation in the other language, but where the French are mostly unable to understand or align three words in Dutch.

Living in a multilingual country means having to deal with political parties “on the other side of the linguistic border”, which use in elections all the clichés and stereotypes possible about the other community. It means to hear the man who has received the most votes from all over the country say that the Francophones are failed profiteers, or some elected Walloons treat the Flemish of primitive racists (yes, it flies high).

Living in a multilingual country means seeing mainly job offers requiring knowledge of three languages (French, Dutch and English) … and finding it perfectly normal, even if one is disappointed.

But living in a multilingual country also means that all consumer products are sold with notices and explanations in at least two languages. For example, our Camembert (French) packaging is written in Flemish and French.

Living in a multilingual country means learning the names of cities in the two main languages because both versions can be used on the road signs of the same road: the city of Waremme will become “Borgworm” and then again ” Waremme “, in less than 10km (it also works with Mons / Bergen, Braine-le-Comte / ‘s-Gravenbrakel and Mechelen / Mechelen).

Living in a multilingual country, which is more important for Europe, means above all being accustomed to evolving in a context where foreign languages and other cultures are omnipresent. We do not necessarily speak the other language perfectly, but we are used to hearing it everywhere, and we get used to it naturally. I would say that the Belgian is, more or less forced and forced, more sensitive to foreign languages.

And I think that all this is a bit of our wealth!

And you? Are you Belgian? Or are you French and not really up to date on the subject of languages in Belgium? Do you see a little clearer now? Tell us !